I didn’t mean to start this series with the Minneapolis (MN) Central Library, it being so close to home. But I used my experience almost-visiting the National Library of Spain as inspiration for my next library visit. Armed with an appointment this time–and a habit of walking into libraries unimpeded–I chose to explore the Special Collections of Minneapolis Central Library.

A little background and disclosure: Tom and I have both been active in supporting the Minneapolis Library. Tom served on the Friends of the Library board in the 2000s, and I helped promote an author series called “Talk of the Stacks.” We were around when the Minneapolis Library and the Hennepin County Library systems merged in 2008, and when the new building of the Minneapolis Central Library (designed by César Pelli) opened in 2006. So I’d heard of the special collections, but it was a bonus to be guided by librarians Bailey Diers and Ted Hathaway.

Entering Special Collections, I found Ms. Diers organizing a stack of clippings. Yes, yellowed newspaper clippings, cut neatly from the daily papers, just as my mother used to do with a special tool that guided the blade straight up the margins. Up until 2001, the library still diligently clipped items from the Minneapolis papers. Their cataloging left a little to be desired, though, so Diers was attaching more meaningful terms and categories than “Minneapolis-General.”

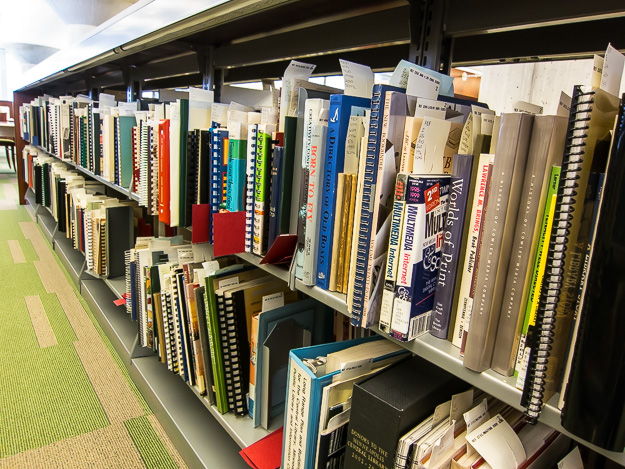

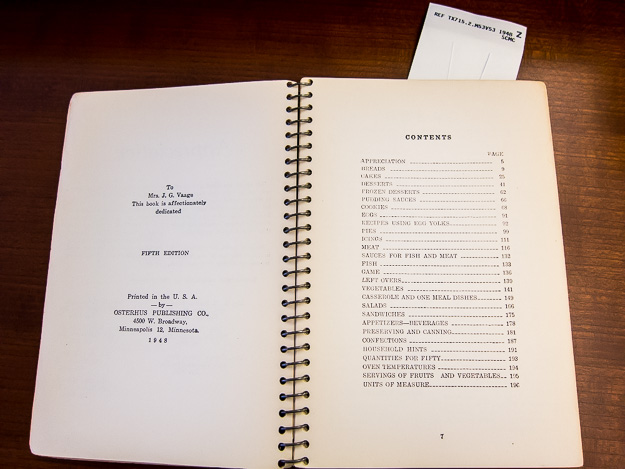

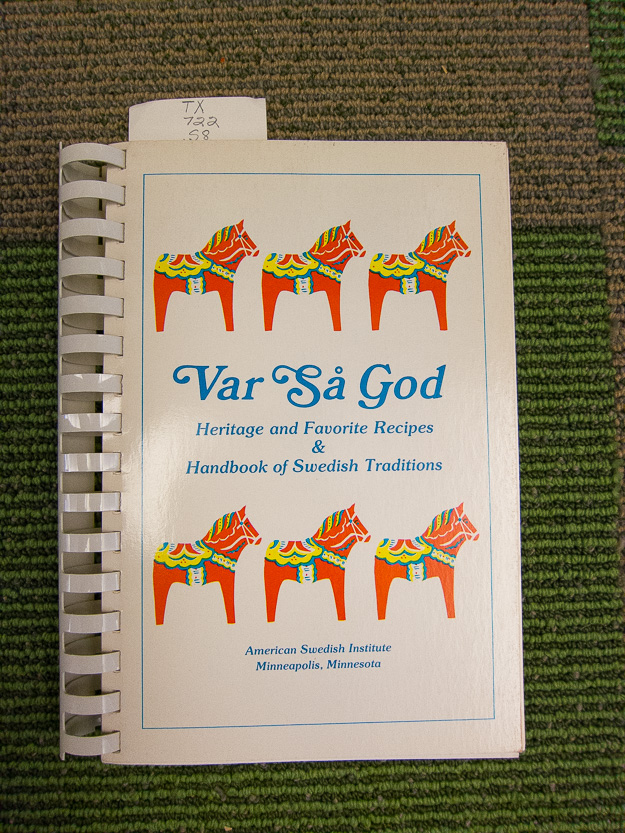

By far the largest section of Minneapolis Central’s Special Collections is the Minneapolis History Collection, with materials including city directories (want to look up someone from the ‘phone book’ of the 1930s?), maps (what were the city boundaries in 1870?), high school yearbooks, annual reports, autographs, art, music, cookbooks, menus, event programs, and again, those yellowed clippings.

Individual donations inspired the other main areas within Special Collections: the Kittleson World War II Collection, the 19th Century American Studies Collection, the Huttner Abolition and Anti-Slavery Collection, the Hoag Mark Twain Collection, and a unique History of Books and Printing Collection. Each of these has its treasures: original documents, personal letters, first editions, irreplaceable photographs, manuscripts, and historic pamphlets and posters.

Secure vaults elsewhere in the library hold much more–stacks of archives, back issues, and more delicate primary materials housed in a climate and humid controlled room.

As Hathaway notes, these collections are “of local origin but of international interest.” The work in Special Collections is endless, digitizing images and creating the metadata to improve organization and access to these special materials. The process doesn’t minimize the source materials, but deepens their stories and maximizes their usefulness.

During my visit, volunteers were, for example, digging up maiden names of women so they could be identified other than Mrs. Insert-Husband’s-Name. The 1901 political cartoons of Charles Bartholomew for the Minneapolis Journal were being digitized and studied to glean their symbolism and context. And with pride, Hathaway showed me the extensive files of Minneapolis Central Library’s early librarian, Gratia Countryman, who was one of the nation’s first librarians to champion extra library services, outreach, and specialty areas in community libraries.

Today, huge personal collections are less likely to be donated, but monetary donations are as important as ever to support digitizing efforts. While Minneapolis Central coordinates its efforts with the Minnesota Digital Library, it still has sole responsibility for the continued gathering, interpreting and preserving of its special collections.

Hathaway points out that the original Minneapolis Library, located just a few blocks from the current site, was a true cultural center. The symphony orchestra offices were there, and the art collection of T.B. Walker (later the basis for the Walker Art Center) was exhibited there, too. These original ‘friends’ of the library supported the library by holding events, attracting visitors, and by donating to the collections.

Although Special Collections is comprised of non-circulating materials–items that are kept in the library to protect and preserve them–surveying book spines and file labels is plenty inspiring. (Start a research project, volunteer, sign me up.) Many of the collection’s materials are available in the main library, and more and more are available online. The rest of Minneapolis Central is bustling, with lots of activity on computers, in meeting rooms, in lofted study areas, in teen and children’s sections, and at the check-out desk. The parking ramp was full, and it is plain to see that Minneapolis Central has remained a cultural center and well as a repository for special collections.